Can You Hear Me Now? Part 4

Trunked Communications.

Tutorial:/ Cameron O’Neil

In the three previous articles in this series we’ve pretty much covered the gamut of communications technologies available to the world of live events. But what about those times when you have to link multiple sites together?

Take the situation of a major-company AGM where they are working across two sites; one in Sydney and one in Melbourne. Each site will have its own production crew with its own communications needs; however you’ll also need to communicate between the two sites in in real time. As the complexity goes up, so do the requirements. Suddenly the video conferencing techs want to have a back-channel to make sure that they have their gear together. The company representatives will want to keep in touch privately, and worst of all, there’s no mobile phone coverage in the Sydney venue, so phones are out of the question.

PHONING HOME

Trunking is a term used in many different forms of telecommunications to indicate longer-haul operations, but in the events and broadcasting world, it refers to linking systems with multiple connections to provide communications between locations. These could include situations such as linking between studio locations, an OB truck and their network master control room, or a multi-venue event like Tropfest, a Papal visit or a sporting carnival like an Olympics or a Commonwealth games.

Originally, this was achieved via standard telco lines known as Order Wires, which a broadcaster or production company would order (alongside the higher bandwidth Program Wire) from a telco specifically for an event. These would usually end up on a standard 4-wire analogue port on a bigger matrix system, giving the system little intelligence. That said, until recently they have been the most cost-effective method of expanding the reach of a comms system. They are still quite prevalent in larger TV productions, especially those that have to reach out to regional areas. You’ll also see mobile phones strapped up in most news crew’s runabout trucks; used as a backup to the main communications line (usually contained within the truck’s satellite or terrestrial video link system).

When telephone network gateways improved, most communications systems switched to ISDN (128kbps) digital telephony lines instead of standard analogue (56kbps) Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) lines. The higher bandwidth of these lines and the ability to use high efficiency codecs resulted in a much higher audio quality. Some comms systems allow control data to be passed through the codec as well, allowing you to place a fully-functional matrix key station in your remote location. Suddenly, instead of calling out to everyone on your comms matrix, you are able to control your communication channels. In effect, we’ve moved the remote station from being a partyline station to a fully-capable matrix key station.

Since high-speed internet has become widespread and reliable, IP-based codecs have been replacing ISDN lines. Just like an ISDN line, this can be used as a standard audio transport line, or as a matrix extension. With the emergence of IP protocols such as IPSec (IP Security) and Dynamic Multipoint VPN, communications engineers are able to make virtual private networks anywhere, simply by putting one of their routers somewhere in the network. These protocols allow a matrix to talk directly to a key panel, no matter what path the internet takes between the two points. Some companies have even started experimenting with AVB-based transport methods, promising ultra-low-latency IP-based communications.

BRIDGING THE GAP

Whilst trunklines are an easy way to extend the reach of a communications network beyond that of standard fibre extenders, they don’t achieve our goal of linking sites together with full functionality. To do this we require two things; a bunch of trunk lines and a data connection.

Almost all modern communications networks allow for multiple matrix frames to be connected locally, usually over coax or fibre. These local connections allow for more key panels and interfaces to be connected with full functionality although the links are usually limited to about 10-20 km.

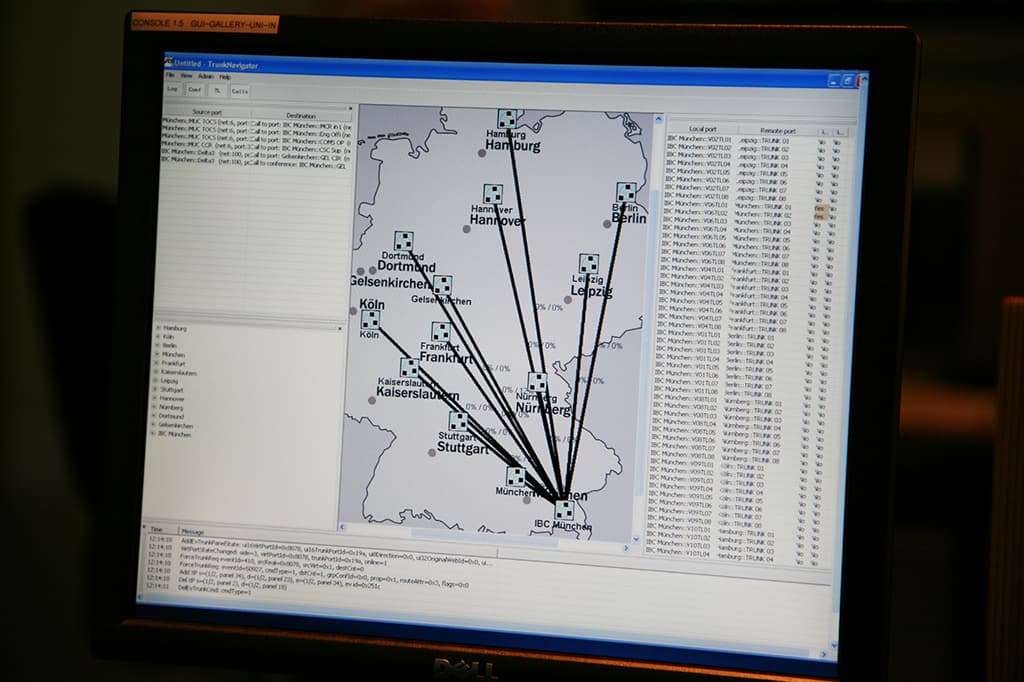

Beyond that we need to ‘trunk’ the two networks together. Most matrix systems allow this to happen, but with varying degrees of functionality. No matter the system, the principles are the same.

The trunked systems must have data links to identify and route the traffic coming over on the audio lines. This enables the users to see what looks like a single seamless system.

The other component is the audio paths which may be analogue PSTN, ISDN or audio over IP, all of which are acceptable on most systems. Since the audio signals are intelligently switched and routed over the trunk link, you don’t actually need as many paths as you would if you individually connected each station to a remote matrix.

There are even interface devices that will allow experienced operators to trunk between two matrices of different makes; for example a Riedel Artist matrix can be trunked to an RTS/Telex Adam matrix via an intelligent interface box.

FINAL CHECKS

Over this series of articles I hope I’ve given you some insight into the world of communications. While to some it may not seem as glamorous as projection or lighting, it is one of the cornerstones of production. Hopefully I’ve shown that there are newer and easier ways to get everyone talking, particularly in the wireless space. With a matrix system you can filter conversations so that only interested parties are taking part in them, and with radios and trunked systems you can extend the reach of your production anywhere in the world.

Every production needs great comms, whether it’s two guys at front of house and a stage manager backstage, or a complex event like the Sydney New Year’s Eve fireworks, with hundreds of people communicating over umpteen trunk lines and multiple matrix frames. While the technology in the other events and production disciplines is progressing rapidly, so too is communications technology.

In short, there’s no reason that the answer to the question I hear daily; “Can you hear me now?” shouldn’t be a resounding “Yes!”

RESPONSES