Track Talk

The 2010 Formula One season is in full swing, with one of the most sophisticated comms systems going around. Andy Ciddor backs his ’86 Laser into the pit lane and throws Bernie the keys.

Text & Images:/ Andy Ciddor

Of all the staff and freelance writers on AV, I was the ideal choice to cover the Australian Formula One Grand Prix when Riedel invited us to see its handiwork at the event. It’s not as if I’m completely inexperienced with motor sports. I have previously been to the Australian Grand Prix when Dad took my brother and I to stand on the grass beside the Albert Park track in the early ’60s to see some very loud cars whizz past. I’m told that one of the blurs was Jack Brabham and that another was Stirling Moss. That first involvement with motor sport failed totally to usurp my interest in electronics and transform me into a petrol head. So much so, that at the time of this visit visit to the Grand Prix, I was still driving a 26-year-old Ford Laser, which I have finally given away on the exasperated advice of my mechanic.

While anyone else on the AV team may have been distracted by the shiny (and extraordinarily loud) F1 cars and the cream of the world’s racing drivers, I was much more interested in just how deeply embedded in F1 racing Riedel has become. Like most people in the industry, I couldn’t help being aware of its involvement in both wired and wireless communications, and talkback systems for such high profile events as the Beijing Olympics and the recent Papal tour. I was also aware of the increasing use of Riedel equipment for comms, and more recently the transport of audio and video signals for outside broadcast. What I wasn’t expecting was the extent of its involvement in the business of data and communications infrastructure for the travelling circus that is Formula One motor racing.

Riedel has long since accepted (as everybody inevitably must), that all data transmission is destined to become a stream of Internet Protocol packets – it is actually an IP datagram trucking company – and got on with building all its products from that standpoint. Once you take that decision, the infrastructure you install and manage can just as easily be handing VoIP, HTTPS, SAMBA, FTP, VPN or PPPoE as talkback, audio, SDI or digital trunked radio. As Riedel’s involvement with Formula One Management (FOM) has deepened over the years, its data management, transport and distribution has become the infrastructure on which the entire event is based.

COMMS: TEAM EFFORT

At the most fundamental level, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) race controllers must have high priority direct communications with each participating team and its manager. Irrespective of the technology or supplier selected by each team for its internal communications, the FIA’s Artist S Ring includes a node and a panel at each team’s pitwall control centre which links into the team’s own comms system. This system also captures and records the audio link with the driver for use in broadcast coverage and race archives. The ‘Team Radio’ feeds used for the race broadcasts are also transported by this Artist network. The ring includes the digital radio links to all FIA course officials, FIA service providers, the Mercedes-AMG medical car, and to Bernd Mayländer in the Mercedes-AMG safety car. An additional backup analogue radio system also connects the FIA race officials, the safety car and the medical car.

Each participating team then has an independent comms system to link its team members in the pit, in the garage, at the pitwall control centre, around the track, the race car when it’s inside the garage, the various motorhomes that serve as offices and accommodation (the resemblance to a circus becomes clearer) and, increasingly, also with a comms panel back at the team’s factory. Much of this involves full-duplex interfaces to both analogue and TETRA (TErrestrial Trunked RAdio) handhelds. The link to the race car on the track is via a customised TETRA terminal that includes a high-noise environment driver microphone and an audio control box that incorporates switching from wired to wireless comms, volume control, and noise cancelling and volume adaptation processing. For the 2010 Formula One season, Riedel are providing these services to eight of the 10 teams.

The communications component of Riedel’s work on the current F1 Grand Prix tour involves the deployment of some 17 Artist S nodes and 26 Artist 32/64/128 nodes, about 210 intercom panels, seven digital partyline systems, each with approximately 20 beltpacks and 35 radio interfaces. There is also a TETRA base station and several repeaters feeding some 800 handheld terminals, two analogue repeater stations with several handheld units, and around 400 customised, high-noise environment Riedel Max headsets.

“”

A team of 10 Riedel technicians travel with the Formula One roadshow throughout the racing year

BROADCAST

Riedel’s Mediornet system, which incorporates real-time signal transport, signal routing and format conversion for SD and HD broadcast video, multi-channel audio, communications and data feeds – all over a single fibre pair – is an integral part of the broadcast system for the Formula One event. FOM’s ‘World Feed’ forms the basis for the television coverage that reaches almost every corner of the planet, making F1 racing one of the world’s most-watched sporting events (only eclipsed by the Football World Cup and Olympic Games). Mediornet provides the links between the heavily-fortified FIA race control area and the equally-well-protected FOM broadcast compound.

DATA LINKS

It’s easy to understand how Riedel became involved in the data infrastructure of the Formula One event. It was already running a 10km fibre ring between all points on the track for communications, race control cameras and broadcast signals, and providing connections into the national telecommunications networks of the host country for links back to the various teams’ offices and factories. So it was only really a matter of doing a great deal more of the same to provide the total data and telecommunications networks for the event.

Riedel provides an event data network that carries information for the FIA document service, the FIA marshalling service and the FIA weather service, out to each of the teams. This includes reticulating and securely recording the feeds from the anti-tampering security cameras that monitor the secured parc fermé (literally: closed park) area where each race car is required to be stored once it has been checked by the FIA stewards.

The event network connects to local telecommunications networks via a 155Mbps MPLS (MultiProtocol Label Switching) link. This enables carriage of a wide variety of data, including documents, engineering data, telemetry and communications links to the factories of the supported teams. It also carries the TV-over-IP feed for the German broadcaster RTL.

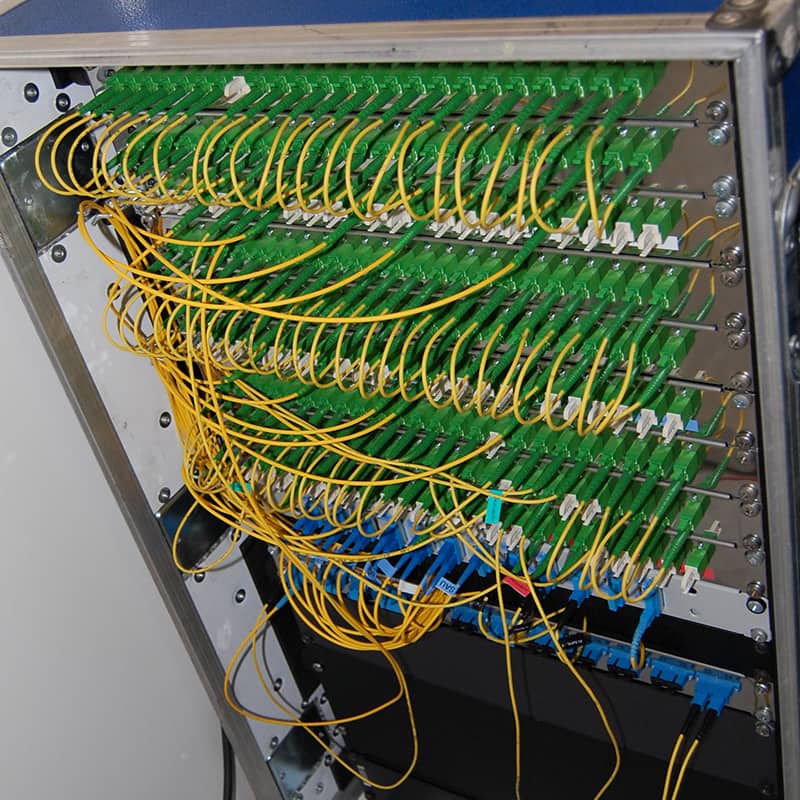

LOGISTICS: KEEP THE MOTOR RUNNING

Under F1 manager Christian Bryll, a team of 10 Riedel technicians travel with the Formula One roadshow throughout the racing year, providing round-the-clock service to the supported teams, in addition to the services contracted to the FIA and FOM. With a requirement for 50 to 60 frequencies to be allocated at each event, Riedel has one person in its head office whose sole job is frequency management and allocation for Formula One. There are also two network technicians who work in advance of the roadshow, supervising contractors to lay and test the fibre at the next track so that everything is in place awaiting the arrival of the thousands of shipping containers, trucks and motorhomes that descend on the venue 10 days before the race, then move out within 24 hours of the finish. To enable the infrastructure to be in place ahead of the arrival of the circus, there are duplicate sets of fibres, patchfields, media converters and routers that leapfrog ahead of the roadshow to allow sufficient time for installation and configuration of a stable network infrastructure.

My conducted tour of the Australian F1 Grand Prix has finally changed my opinion of motor racing. While it’s probably too late for me to become a petrol head like my rally-driving brother, I can at least appreciate the complexity of the technologies that hold motor racing together.

RESPONSES